Passports Without Pictures

- 2025. g. 12. jūl.

- Lasīts 3 min

You’ve probably also come across an old passport without a photograph—just a thumbprint instead. One of Aleksandrs Pelēcis’s stories explains the circumstances under which such photo-less passports were issued.

In the summertime, I sometimes spend a few days in a small town, flipping through old books from my grandfather’s shelves. This week, I got completely caught up in Aleksandrs Pelēcis’s childhood stories from Mālupe parish. One short tale in particular vividly illustrates how passports were issued to farmers. Judging by the description of the passport, it likely took place around 1926, when Latvia began issuing booklet-style passports. I’m sharing a shortened version of the story “Passports for the Poor” (Latv. "Nabagu pases")—you’ll find the full version in the book!

Once Ķikši (the homestead – AL) had been divided, it came time for all Mālupe residents to receive new passports—those steel-gray booklets with the state’s coat of arms on the cover. In that coat of arms, a lion and another beast were raised up on their hind legs. Very fine-looking booklets indeed. ut to get the passports, the local messenger brought notices to everyone to come to the parish house at a certain time. There, a photographer would be waiting, and for one lat per person, he’d take a portrait for the new passport. (...)

Those who wanted and had more money could even have a chest-up portrait or a full-body photo taken. The artist even had a "decoration" to place behind you, so it looked like you’d been photographed at a palace. But no one from our house wanted that palace. It was enough to get six small portraits for one lat. Only two were needed for the passport—the other four could be given to relatives or friends “in eternal remembrance.” (...)

But here was the issue—Jūle and Andris also needed passports, which meant another lats was required for each of them to get their photos taken. But where would they get the money? The farm had been divided, the granary key handed over. Not a single santīms in sight. Otte and Alekss agreed—they had to come up with something to avoid such unexpected expenses for their parents. One neighbor, probably Jūlijs from Rēpši, had joked at the creamery:

“Poor folks will be getting passports without photos...”

That gave them something to think about. What if they got a certificate proving that Jūle and Andris were without movable or immovable property—in other words, indigent?

So Alekss, on his way to the creamery, spoke with the parish clerk, Brilts:

“Here’s the thing! My brother and I have elderly parents at home. They’re weak and have given up all possessions. Could they be issued a certificate of poverty? Then we wouldn’t have to spend money on a photographer…”

The clerk gave Alekss a strange look, but after he had gone, smirked and told the secretary:

“Well then, write out for those brothers that their father and mother are paupers, so they don’t have to shell out two lats…”

The clerk reminded him:

“But next week the father and mother still have to come to the parish house—there needs to be a signature and a thumbprint in the passport…”

Then the day came for Jūle and Andris to go get their passports. (...)

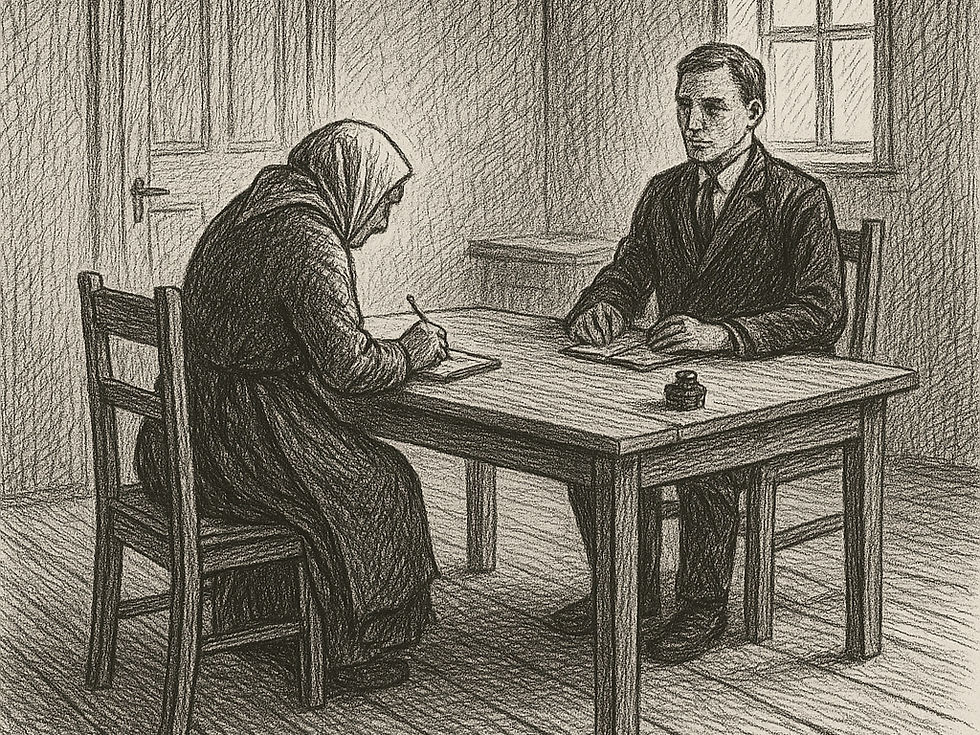

Andris added that he wouldn’t go in with Jūle at the same time. Sure enough—he wandered off to look at the German fir trees, while Jūle dipped her thumb in soot and wrote the only word her grandson had managed to teach her: Jūle…

Instead of a passport photo, there remained a thumbprint and a clerk’s note stating that, due to the owner’s poverty, the document was issued without a photograph. Then Andris did the same. He knew how to sign and proudly wrote Teter, even adding a flourish at the end…

And so the matter was settled without spending any money, and the father and mother legally received pauper passports. The brothers proudly told how cleverly they had managed it. But then the jokes began. Now the whole Žērveļi village wanted a refund for the lats they had paid for their own parents’ passports. They went to that same Brilts:

“Here’s the thing! You gave those certificates to the Teters, and they got passports for their parents without paying. Now we want our money back too, because our parents also have no property…”

The happiest were the lazier ones who hadn’t yet gotten passports for their parents. They all got poverty certificates for their fathers and mothers, and in Žērveļi village, there ended up being about a dozen such paupers… (...)

Aleksandrs Pelēcis “Puisisiska dvēsele”, Rīga “Liesma” 1990